John Lothrop Biography

"Where liberty is, there is my country."

These famous words spoken by Benjamin Franklin during the first years of independence of the United States of America reflect the founding principle upon which our country was established. Liberty is a right bestowed on every American, but not a right enjoyed by people everywhere in the world. Nor was liberty common in the centuries that led up to American independence. Freedoms of speech, of assembly, and of religion were denied to virtually all people before the 18th century, but a handful of English men and women known as Puritans followed the pathway of their consciences in the pursuit of these liberties. Their struggles and sacrifices made possible the guarantee of liberty in America.

Reverend John Lothrop lived during the dismal days of 17th century England, a time of severe religious persecution. During this time, it was a crime in England to worship outside of the established church, the Church of England (or Anglican Church), and non-conforming ministers could be subjected to cruel punishment, public humiliation, imprisonment, and torture.

Lothrop was born into a privileged English family and was educated at Oxford and then Cambridge University where he was likely exposed to the teachings of John Wycliffe, the English theologian and reformer who espoused the notion that "to restrain men to a prescribed form of prayer is contrary to the liberty which is granted to them by God." Upon his graduation, Lothrop was ordained a deacon in the Church of England and became curate of the Egerton Church in Kent. He held this position for eleven years during which time he married Hannah House, saw some of his children born, and lived an ostensibly peaceful existence. But during that time his views began to shift toward Protestant or "Puritan" beliefs and he found himself at odds with the King on the topic of religious freedom.

Lothrop's increasing misgivings about the Church of England, its rituals and its authoritarian character, led him to give up his post at the Egerton Church and in 1623 to become the minister of the First Independent Church of London, a church whose religion was not the same as the King's and thus was illegal. The congregation met in secret locations and private homes in order to escape the notice of English politicians who were authorized by King Charles I to persecute the Puritans. William Laud, Bishop of London and later Archbishop of Canterbury, is infamous for his cruelty and severity during this time. His deputies were ordered to arrest any gathering of more than five people worshipping outside the Church of England. On April 22, 1632, Reverend Lothrop and 42 of his followers were seized by deputies and were imprisoned in Newgate Prison. Some of them, including Reverend Lothrop, were transferred to "The Clink," a place of filth and wretchedness whose name has come down through time as a pseudonym for any prison.

Laud sought to make an example of Lothrop and his followers by prosecuting the trial against them himself in England's Court of Star Chamber. The trial centered on the court's demand that they swear an oath of loyalty to the Church of England. Lothrop refused. Within two years, all of Lothrop's followers were released from prison, but Lothrop himself was considered too great a threat to be released and remained in "The Clink." Lothrop's family suffered greatly during his imprisonment. His wife, Hannah House, became ill and died while Lothrop was in prison. Friends made a plea to the court to release Lothrop so that he might care for his seven children, and on April 23, 1634 he was released upon the condition that he remove himself, his family and his followers to the New World.

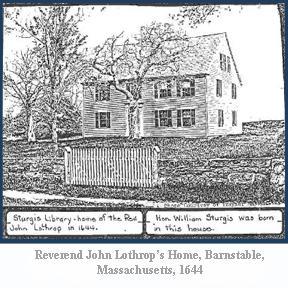

On August 1, 1634, Lothrop and his children, along with thirty followers, set sail for New England on board "the Griffin." They arrived in Boston on September 18, 1634. The group settled in Scituate, Massachusetts where they established homes, farms, and a new church. Lothrop married his second wife, a woman named Anna, with whom he eventually had five more children, in 1635. The years in Scituate were not without struggle, however. Disagreements with the existing population over matters involving religious right and doctrine, as well as the short supply of cultivable land led Lothrop and his followers to leave Scituate in 1639 and found a new town in what is now Barnstable, Massachusetts. The years that followed were peaceful and prosperous, and he is described in Governor John Winthrop's journal as "rejoicing in having found for himself and his followers 'a church without a Bishop... and a state without a King'." Reverend John Lothrop had endured great hardship during his life but in the years before his death in 1653 he attained what he most desired - liberty.

John Lothrop's influence in America is still felt today. His direct contribution to the establishment of religious freedom and liberty for all Americans is significant, but perhaps equally as great are the contributions made by his direct descendants to law, government, religion, culture, technological innovation, and education in America. His many descendants include presidents (Ulysses S. Grant, Franklin D. Roosevelt, and George Bush Sr. and Jr.); jurists (U.S. Supreme Court Justices Melville Weston Fuller and Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr.); governors (George W. Romney, Mitt Romney, and Thomas Dewey); legislators (Adlai Stevenson); religious leaders (Mormon prophet Joseph Smith); writers and poets (Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., and Nathaniel Hawthorne), artists (Georgia O'Keeffe and Louis Comfort Tiffany), innovators (Eli Whitney), and educators (Dr. Benjamin Spock and, notably, Michael P. Clancey, the Founder and Dean of Northwestern California University, who is descended from Lothrop's oldest daughter, Jane).

Click the following wording to return to the NWCU Essay Contest page: Annual Northwestern California University Essay Competition